What good is a geologist in war?

In the last few months I’ve had many discussions with people about the history of the Earth Sciences – geology, geophysics, oceanography, and more – and how the emergence of these fields as respectable and important scientific institutions is tied directly to major political events in the twentieth century. With that in mind, I’ve decided to write a series of posts elaborating in depth on this topic: how the rise of oil and the experience of WWI changed geology, and how WWII and the Cold War shaped oceanography, and how we still feel the effects of these events in the field today.

We cannot ignore the influence of human history on how humans study science if we want to be good scientists, and I am HERE TO HELP! This first post is about geology and the early half of the twentieth century, featuring the professionalization of the sciences, the rise of oil, and the First World War.

Fig. 1: Example of a military geology cross-section presented to a commanding officer during World War I.

Professionalization, or “How to Make Your Science Respectable”

The story of geology from 1900 to 1930 is the story of how the field became transformed from an exclusively observational activity carried out by researchers carefully mapping outcrops across the wildernesses of the world to a professional pursuit closely intertwined with governmental and industrial interests. Over the course of five decades, American research in earth science developed rapidly, largely due to the benefits it received from the oil industry and the military.

When I refer to “professionalization,” I am referring to attempts by many scientists within their fields to have science be seen as an occupation rather than a habit curated by the wealthy and privileged of the world, as its contemporary reputation suggested. Professional scientists as we know today did not exist, nor did they receive the financial support that most of us require. The transformation of science from a pursuit of the elite as a leisure activity to a massive endeavor with publicly transmitted results and large groups of people working together in an institutional setting was so critical and so unprecedented that many scientific historians refer to it as “the second scientific revolution.”

At the turn of the 20th century, scientists across the world were organizing themselves on unprecedented scales to ensure better data sharing, and earth sciences were no different. This in turn brought a sense of professional identity and self-description of their roles in ways that hadn’t really existed before – for example, the United States Geological Survey and the American Association of Petroleum Geologists sprang into being in the early 1900s. These organizations were very small in the beginning (less than a hundred members in each), but they busily began “professionalizing” geology – petroleum geologists claimed their role was to “ensure a reliable supply of oil” for the United States, giving themselves a noble purpose (and a reason to be asking for funding). Organizations like the USGS and AAPG seem commonplace now, but the level of communication they facilitated was incredible at a time when most scientists were struggling with how to keep pace with the speed of technological developments and research findings around the world. Professional organizations lent geologists credibility that allowed them to expand their ranks, gaining further credibility in the process.

Fig. 2: AAPG's goal of finding a reliable supple of oil was bold: new classes of warships like the HMS Dreadnaught were some of the first to be powered by oil, and oil companies had to find ways to power them all.

The geologist’s leap to a position of authority was aided by the concurrent professionalization of the oil industry from a luck-based, “wildcatting” field to one that required scientific precision to sustain itself. This transformation was contemporaneous with the U.S. Navy’s decision to convert its fleet from coal to oil in four years, beginning in 1910. The government’s sudden demand for massive quantities of oil placed the burden on geologists to find it. Correspondingly, innovation occurred within the oil industry out of pure necessity. Geologists began utilizing new technology and developing new methods such as bottom-hole sampling that measured properties like temperature, viscosity, and gas saturation for the first time. After the war a burgeoning paranoia began that the U.S. would “run out of oil,” and the industry was forced to respond, beginning to focus on improving its recovery techniques to maximize volumes. We have been acutely afraid of running out of oil for almost as long as we have been dependent on it, and it is a fascinating interplay that has driven many of the innovations in geology and geophysics that we respect today.

The oil industry’s new quantitative, instrumental focus (largely inspired by governmental demand) arguably changed the course of earth sciences in the U.S., as American geoscientists turned increasingly towards the new field of geophysics and land and marine seismic surveys. Over the next several decades, American geophysicists made a name for themselves in the international community as “the numbers people,” generating gobs of data in the form of seismological and pressure tables. As the oil industry became more closely tied with the U.S. government, geologists outside the industry found themselves being pulled into the political orbit as well, largely due to the nation’s experience in World War I.

“We are Called to Serve” – Geologists and the War Effort

The advent of World War I transformed American industry, essentially jump-starting the oil industry machine as we know it today. However, it also fundamentally changed the direction of many scientific fields as the government scraped up scientists in droves to help with the war effort in any way they could, calling on their patriotic duty and plying them with research funds. Researchers from the highest echelons of academia found themselves engaged on both sides of the war; the chemists who developed mustard gas would win Nobel prizes years later, engineers made enormous strides in radio technology, and geologists followed suit (albeit a bit slower).

When we think of scientists helping their countries in WWI, we typically think of men in lab coats standing under the watchful gaze of military supervisors. While this is in many ways not an inaccurate depiction, the journey of geologists in WWI was a very different one that is tied far more to the actual field of battle.

It is common knowledge that when World War I began no one was ready for the form it took, or the fundamental ways in which the tactics displayed and the scale of the terrain were different from any war experienced before. Trench warfare was a new phenomenon, and success in trench building became increasingly critical as the war limped on. The Germans were slightly more prepared in this regard as they had already employed “war geologists,” or Kriegsgeologen, prior to the beginning of the war to acquire geologic and topographic maps of France and the surrounding nations. The British, in contrast, lacked basic geologic and topographical maps (the only British copy of a geologic map of France at the time was in the London Museum) and had to scramble to commission geologists to do what would be the most dangerous fieldwork of their lives.

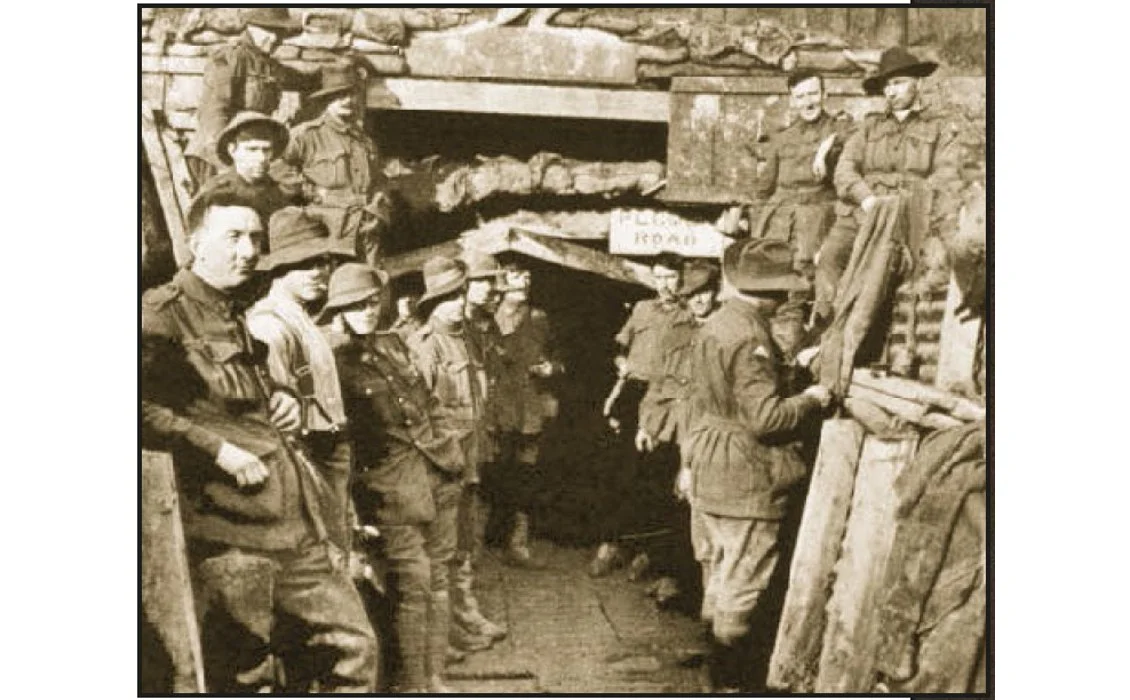

Fig. 3: Geology was not all passive work - pictured here are the Australian geologic corps, whose efforts culminated in the most lethal, non-nuclear explosion in the history of war, and was the largest planned explosion in history until the 1945 Trinity atomic weapons test.

American geologists were not immediately recruited into the war effort, however, and many prominent scientists took umbrage, petitioning the military to make use of their obvious skills (though the military clearly did not think of their skills as “obvious”). USGS scientist R. A. F. Penrose penned a twenty-page pamphlet entitled “What A Geologist Can Do in War,” leaving copies of it for the military brass to encounter. In it, he extolled the virtues of the geologist:

“[A geologist's] training has been in the wilds among mountains, hills, and plains...where he has had to take his course... from the stars… He can fight, cook, withstand bad weather and discomfort, and still keep on with his scientific work.”

That’s some bold words. Was Penrose motivated by patriotism, or by the opportunity to raise the stock of geology as a legitimate science? While it is difficult to tell, his words appear to have had some effect as America geologists were recruited and shipped overseas soon after.

We know what Penrose thought geologist can do in war (i.e., be the Rambo of the science world), but what did they actually end up doing? Most military geologists were commissioned by various army groups to produce geological surveys and topographical maps, as well as describe locations of underground water sources (for wells) and road metal (gravels and other material that could be used to build quick roads). Their other focus was to determine where the best trenches could be dug. Location mistakes in trench building, such as digging down into hard granite or into a shallow water table, had fatal costs in battle if men were stranded without a trench to duck into. The military grudgingly admitted that they needed this geologic information, and needed it without delay.

Fig. 4: A military geologic map produced by USGS and military geology corps member Alfred Brooks, describing the possibilities for trench construction.

I cannot emphasize how important the experience of military geology was for the later development of earth science in the U.S. This was the first real meeting of the minds for earth scientists and the military – the moment where each realized the other’s potential benefit. World War I was the first of many interactions between the two, and the relationship would only deepen over the following decades. In the short-term experience of the war as well as afterwards, military and scientific perspectives often jarred; the military expected instantaneous reports and results, while geologists stuck to thorough science at a slower pace, particularly now that lives were on the line. Geologists fumed at their superior officers in command tents, but were also deeply aware of their situation as opportunity to prove themselves invaluable.

The fundamental disconnect in military versus scientific perspectives did not prevent a partnership, but as the cooperation continued into the interwar years, it produced a perennial suspicion that one group would not follow through on requests unless the other was constantly supervising.

What Comes Next?

The end of World War I left behind a world transformed, and the earth sciences had changed with it. The first decades of the twentieth century saw remarkably quick development in American earth science, particularly in geology and geophysics. Such development was made possible by deepening ties with the oil industry and the U.S. military, which funded research in exchange for scientific involvement on their relevant projects. While this system was clearly benefited everyone involved, the scientists began to feel trapped in a net of obligation. They were certainly aware that they were forming the beginnings of what some have termed the “Academic-Industrial-Military Complex,” a nexus that began in the First World War but blossomed after the second with the inauguration of the Cold War.

Geology and geophysics continued to develop under the watchful eye of their new partners, but my next focus for WWII and the Cold War will be on another science that falls under earth science: oceanography. Oceanography also has an interesting story, particularly in its close ties to the U.S. Navy, the problems associated with that, and the amazing scientific discoveries that results.

That’s all for now! Tune in next time for Part Two of Evolution of the Earth Sciences: I Swear this Underground Array is for Science, Not Soviet Submarines. And don’t forget the moral of this post – science does not exist in a vacuum. I’m here to help you realize that it never has.

Selected References

Brooks, Alfred H. "The Use of Geology on the Western Front." USGS Report 1919.

Macleod, Roy. “ ‘Kriegsgeologen and Practical Men’: Military Geology and Modern Memory, 1914-18.” The British Journal for the History of Science, 28.4: Dec. 1995. 427-450.

Penrose, R.A.F. “What a Geologist Can Do in War.” Philadelphia, J.P. Lippincot: 1917. 1-40.

Shulman, Peter A. “‘Science Can Never Demobilize’: The United States Navy and Petroleum Geology, 1898-1924.” History & Technology 19: 2003. 365-385.

Van der Kloot, William. “April 1915: Five Future Nobel Prize-Winners Inaugurate Weapons of Mass Destruction and the Academic-Industrial-Military Complex.” Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 58: 2004. 149-160.